| Cold comfort | Damien Ihrig, MA, MLIS

Curator, John Martin Rare Book Room

Happy December, friends. Another year is in the books, and as George R. R. Martin once famously said, "Winter is coming." Okay, it may have already arrived in Iowa City. Happy December, friends. Another year is in the books, and as George R. R. Martin once famously said, "Winter is coming." Okay, it may have already arrived in Iowa City.

With winter comes snow and frigid temps, of course. As you walk around, breathing in the crisp air and having your face go numb from the wind and snow, you may think to yourself, "Hmm, I wonder if anyone ever considered using snow as anesthesia?" The answer is a stone–cold "yes."

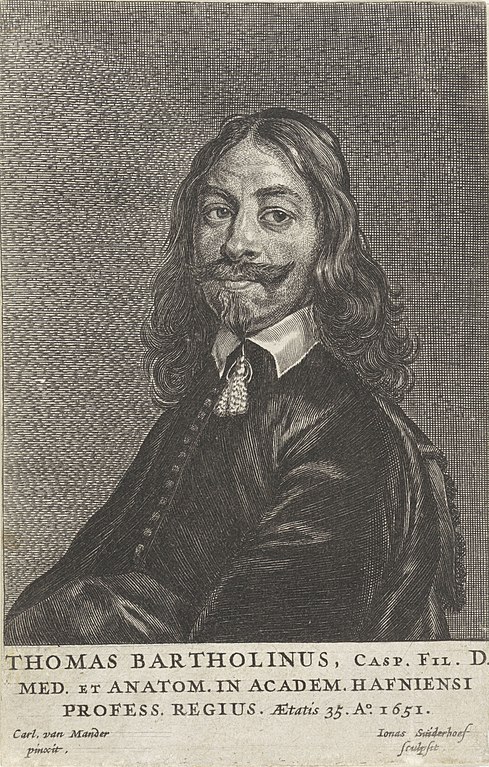

This month, we highlight a work from the prodigious 17th–century Danish physician Thomas Bartholin (1616–1680). Bartholin emerged as one of the most famous members of his incredibly academic family. He followed in the footsteps of his famous physician father, as his son would later follow in his.

Beyond looking like Billy Joel in his heavy metal days (yes, that was a thing), Bartholin rocked a strong scientific mind and was a prolific writer. He corresponded with many of the greatest thinkers of his day, wrote over 20 books (including one on unicorns!), and conducted many experiments.

One area he dabbled in was refrigeration anesthesia (the application of cold to deaden sensation, known today as cryoanesthesia). The application of something cold has long been known to help reduce pain. Medieval physicians, such as Ibn Sina, were the first to write about it.

In De nivis usu medico observationes variae [Various observations on the medical use of snow] (1661), Bartholin picks up where those medieval writers left off, thoroughly examining all the medical applications of snow, including as a topical anesthetic.

Read below to learn more about Bartholin and our copy of De nivis usu medico observationes variae.

Stay warm and happy reading!

Hours

The JMRBR is open to the public from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Thursday and by appointment on Friday. For more information, please contact me at damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154. | | | | BARTHOLIN, THOMAS (1616-1680). De nivis usu medico observationes variae. Printed in Hafniae [Copenhagen] by Matthias Godiche for Peter Haubold [bookseller], 1661. 16 cm tall.

Born into a family of distinguished scientists and academics, Bartholin was the second of six sons of Caspar Bartholin the Elder, a prominent physician and anatomist. The Bartholin family, including Thomas's brother Erasmus and his son Caspar Bartholin the Younger, made significant contributions to anatomical medicine.

Thomas Bartholin's academic journey took him across Europe, where he studied under various scholars and earned his medical degree at Basel. He was known for his reluctance to settle in Copenhagen, preferring the intellectual environments of Leiden and Padua and their tolerance for the critique of traditional Galenic medicine. Despite this, he eventually returned to Copenhagen, where he became a professor of anatomy and mathematics.

In 1652, Bartholin published the first comprehensive description of the human lymphatic system, a discovery that sparked a dispute with Swedish anatomist Olof Rudbeck over who discovered it first. Bartholin's work, however, was widely recognized, and his terminology for the lymphatic vessels, vasa lymphatica, remains in use today. He also coined the term Ossa Wormiana for the irregular sutural bones of the skull in honor of his uncle Ole Worm.

Despite his achievements, Bartholin faced criticism from contemporaries like Jean Riolan (the younger), who dismissed the importance of the lymphatic system. Riolan, an avowed Galenist, was also a strident critic of William Harvey. Someone should have advised him how to better pick his battles!

In his later years, Bartholin retired to his estate, Hagestedgård, which burned down in 1670, tragically destroying a substantial library of manuscripts. King Christian V of Denmark compensated him by appointing him as his | | | physician and exempting his farm from taxes.

Bartholin's health declined in 1680, leading him to sell the farm and return to Copenhagen, where he passed away. His legacy is commemorated in Copenhagen, with a street named Bartholinsgade and the Bartholin Institute.

Bartholin's contributions extended beyond anatomy. His diverse interests led him to write on various medical conditions, historical topics, and even mythical creatures like unicorns. The horn of a unicorn (which many still considered a real animal) was thought to contain potent healing qualities, although the horn Bartholin described turned out to be a walrus tusk.

Regarding De nivis..., Chapter XXII makes the first known mention of the use of mixtures of ice and snow for freezing to produce surgical anesthesia, crediting the Italian physician Marco Aurelio Severino for the technique. To avoid killing the tissues and causing gangrene, the ice–snow mixture was to be applied in narrow parallel lines to the area designated to be cut. After a quarter of an hour, feeling would be deadened and the part could be cut without pain.

Along with about 200 pages detailing all the medical properties of snow (who knew there were so many!), there is also a treatise on snow crystals by Bartholin's younger brother, Erasmus. This is the earliest publication on crystallography and preceded Boyle's Essay about the origine & virtues of gems (1672) by eleven years.

Our copy is covered in a slightly battered limp vellum cover with small yapp edges covering the foredge of the textblock. There is no major damage to the cover, but it definitely looks well–used! Inside, the paper is still sturdy but shows quite a bit of foxing and paper discoloration. Clearly, the water used to make the paper was not as pure as the driven snow.

Contact me to take a look at this book or any others from this or past newsletters: damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154. | | | |